Ivor Bertie Gurney (1890–1937) was an English poet and composer, particularly of songs. He spent long periods of his life in mental hospitals.

The following biography is from the brilliant disabled lives blog. It is reproduced here in full as it is so beautifully written and considered. The pictures, images and photographs included have been added by Peter Gordon.

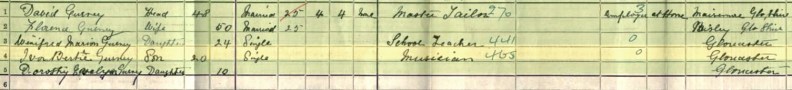

Ivor Bertie Gurney was born in Gloucester on 28 August 1890: his father was a tailor, and he came from humble origins. His mother was highly strung and somewhat unstable.

Florence Lugg, mother of Ivor Gurney:

A local clergyman, Revd Alfred Cheesman stood godfather to Ivor, and later took him under his wing, fostering his ideas and encouraging him. Gurney was a chorister at King’s School, Gloucester, and studied music with the organist, alongside Herbert Howells and Ivor Novello. Both Gurney and Howells were inspired by hearing Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis at the 1910 Three Choirs Festival.

Gurney went on to a scholarship at the Royal College of Music in 1911, supported by Cheesman. There he was considered erratic but brilliant. He started setting poems to music, and began writing his own. At RCM, he met Marion Scott, who was to be so influential in his life. In 1912, came his first mental breakdown: “The Young Genius does not feel too well and his brain won’t move as he wishes it to”, he wrote to Marion Scott. This seems to have been the first in a life long series of episodes of manic depression.

In 1912, came his first mental breakdown: “The Young Genius does not feel too well and his brain won’t move as he wishes it to”, he wrote to Marion Scott. This seems to have been the first in a life long series of episodes of manic depression.

However, by July 1914 he was able to write to his friend Harvey:

Dear Willy, It’s going Willy. It’s going. Gradually the cloud passes and Beauty is a present thing, not merely an abstraction poets feign to honour. Willy, Willy, I have done 5 of the most delightful and beautiful songs you ever cast your beaming eyes upon. They are all Elizabethan – the words – and blister my kidneys, bisurate my magnesia if the music is not as English, as joyful, as tender as any lyric of all that noble host.

When war broke out in 1914, Gurney volunteered, but was initially turned down because of his eyesight. In 1915, he was accepted and served as a signaller with the 2/5th Glosters.

On the Western Front he found it was easier to write poems than to compose music. His was a private’s war poetry, verses about longing for home, dodging tough jobs and the joy of sleeping on clean straw.

On the Western Front he found it was easier to write poems than to compose music. His was a private’s war poetry, verses about longing for home, dodging tough jobs and the joy of sleeping on clean straw.

His first book Severn and Somme was published in October 1917, thanks to efforts by Marion Scott. That year he was first shot in the arm, and then gassed, and was sent home to recover in an Edinburgh hospital, where he fell in love with a nurse.

In 1918, he showed renewed signs of mental illness, with talk of suicide. He spent time in hospital in Newcastle, Durham, and Warrington: his Scottish sweetheart broke with him. He was discharged from the army and sent back to Gloucestershire, where things improved. In autumn 1919, he tried to take up where he left off at the Royal College of Music, but was too restless to settle. There was much roaming and walking.

A second volume of poems, War’s Embers, was published. He worked in a series of jobs musical (organist, cinema pianist) and manual (farm labourer, tax clerk), but money was scarce. He wasn’t sleeping much, but the verse was flowing through the years 1919-1922. He found physical exertion – working, walking – essential therapy for his nerves and the voices and radio waves which he felt were persecuting him.

He tried living with relatives – a brother, an aunt – but neither worked out. In September 1922 he was committed to Barnwood House, an asylum in Gloucestershire, after going around asking for a revolver to shoot himself with. He wrote letters to everyone begging to be released, and tried to run away. Worse was to come when Gurney was then moved away to the City of London Mental Institution in Dartford in Kent. He remained there for the final 15 years of his life, and would never see his beloved Gloucestershire countryside again.But he continued writing, and produced some of his best war poetry.

It would be easy to think of Gurney like poor Septimus Smith in Mrs Dalloway, driven mad by the war. But in truth, Gurney’s mental illness predated the conflict. His behaviour was mainly more eccentric than insane: he couldn’t hold down a job, his sleeping and eating patterns were erratic, he liked midnight rambles. Three-quarters of his poems show no signs of mental illness. His friend Marion Scott described him as “heart-breakingly sane in his insanity”: she left instructions for everything that he wrote in the institution to be preserved and sent to her.

Gurney wrote 200 songs and 300 poems: he was one of the very few artists who have excelled in two forms. The revival of interest in him in the 1930s and after the war was due partly to the loyalty of his supporter at the Royal College of Music, Marion Scott, but mainly to the efforts of the composer Gerald Finzi and his wife Joy. First, they organized an edition of Music and Letters devoted to Gurney, published in 1938: it contained tributes from Vaughan-Williams, Walter de la Mare and others. By this point, Gurney was unable to grasp what the volume represented: a month later, he was dead of tuberculosis. Finally, he returned to his beloved Gloucestershire to be buried.

The last photograph of Ivor Gurney:

Gerald Finzi on Ivor Gurney: “All his work, even the worst, seems to have (for me at any rate) the sense of heightened perception which makes art out of artifice.”