This is the opening chapter of the history of Glen Girnoc(k). Nobody (it is almost safe to say) has heard of this glen. However it is where my Gordon family came from. The glen nestles in Royal Deeside: between Balmoral (Scottish home of our Queen) and Birkhall (Scottish home of the Prince of Wales).

Deeside Tales can be purchased here (the author makes no profit)

All drawings and sketches by Peter J. Gordon, except the watercolour below which is by Howard Butterworth.

Chapter 1: Dwine’t awa an Deid

The Highland Clearance – we know the history; and why should it be any different for this small glen? Well just for now take my word, the Girnoc has a rather special story, and its clearance was utterly unique to its Highland homeland.

As writer of this book I acknowledge here that I cannot match Amy Fraser Stewart’s ‘Hills of Home’ which in my opinion remains unsurpassed in breathing the life into a glen facing extinction – in that case Glen Gairn. Amy Stewart’s book was spell-binding for her childhood recall of a way of life long gone. I have no such fortunate vantage; I am simply, an odd-job historian, without the Doric that I so dearly wish. Yet I feel that my family place in the Girnoc is as spiritual and free as any before, and that my cast is centuries, not decades. Perhaps then I am a talisman (of sorts) for the glen, garnering the voices on its braes; voices which reach out from the heather and bracken, and search desperately beyond the barricaded and shuttered windows of now ghostly farmsteads

“There’s Naebody noo in the glen – lang since dwine’t awa. Dwine’t awa an deid.”

In this book I hope to resurrect the glen as it was in days of bustle, bring back its glory and sorrow, and retrace the dying footsteps of its inhabitants. It is an ambitious cast of many centuries but is a journey worth taking, and just perhaps, it will entice you to walk the glen and to become with me the inextricable.

The first exercise must be to annotate you to the small glen. As stated in the ‘Introduction’ the Girnoc glen is neighbour, and runs parallel to, the larger Glen Muick, separated by the mighty range of the Coyle mountains. The Girnoc can be approached from three directions; two by road, and one by mountain track. The true approach is from Woodend, a woodland copse at the foot of the Girnoc huddled around the bridge and Littlemill. It is here that one finds the salmon trap, and the soon to be erected eel-trap. Woodend of Girnoc is approached from theSouth Deeside Road, crossing theDee at Ballater.

The other approach is from behind Bovagli – to do so you must cross theDee at Balmoral and follow the signs for Lochnagar Distillery. Rising high behind the distillery is a private road to Buailteach, at the end of which is the Deer gate to Bovagli, passing en route Tilfogar, and the Genechal.

The last approach is by the mountainous track from Inchnabobart which brings the back-packer past the castle of the old women, the Castel na Caillach, to the ancient copse of Bovagli. Inchnabobart has a long association with the Girnoc. It was here that in the late eighteenth century that the smugglers used to stop under the genial host John Robbie a man of quick wit who had ‘no liking’ for excise men. Inchnabobart had ceased to operate as an Inn by 1841 but nevertheless must be celebrated here, for sitting at 400 metres above sea level it was by far the highest Inn to be found in Scotland. Inchnabobart now has infamy of a different sort – as Prince Charles’ Royal Howff.

For this book I am going to introduce the Girnoc from Woodend. The journey starts at Littlemill, where a solitary gable hangs over the little rushing burn like a giant smokeless lum. Hidden behind, and nestling the contour, is Littlemill, once home of the Engineers and Inventors of Deeside. On the other side of the Girnoc Brig, following the track through the plantation of Woodend, you come to the modern house of Girnoc Shiel. Here lives the ‘Grand Lady of the Glens,’ Dr Sheila Sedgwick, local historian and author of, amongst others Legion of the Lost and Recalling Glengairn. It is right that Dr Sedgwick lives so close to the Victorian Girnoc Schoolhouse – for she is truly the authority on the area and is the academic who everyone returns to when investigating upper Deeside. Dr Sedgwick is the curator of the Kirk Sessions for Glenmuick, Tullich & Glengairn, as well as those for Crathie.

A short walk from Dr Sedgwick’s house, southwards along the tumbling Girnoc brings thetraveller to the Cosh Mill. These days the wheel is gone – but there are still folk in Deeside who remember it. The Mill of Cosh is aptly titled for in etymological terms this is the ‘mill of the hollow’. It occupies a flat basin at the foot of the Girnoc between the fir covered Creag Ghiubhais (the Sister Hill) and Creag Phiobaidh (Rock Hill of the Piping), both peaks that rise above 450 metres.

Just beyond Mill of Cosh, and through a native birch wood, one comes to the deer gate at the southern end of Girnoc. At this point the track, consisting of no more than bare rubble and sand, rises and curves up towards Lochnagar, though it is not until the Scots Pine trees (Pinus sylvestris) of the Lynvaig copse appear that one gets a view of the majestic mountain. Just before you reach deserted Lynvaig the rickles of lost Newton of Girnoc lay scattered to the east, in rabbit shorn grass. At Newton it is just possible to see the footprints of at least five longhouses and beyond, a track that sweeps down towards the little rushing burn through a wonderfully delicate native birch wood (Betula pendula) which bedazzles in prolific lichenous growth. Lost in the heather on the other side of the burn is Linquoch – it was a settlement abandoned late in the eighteenth century and its history almost totally lost. These days it may only be the salmon-trackers that ever come across it, as it is the only Girnoc community to have been located on the eastern side of the glen. The heather has reclaimed an old track, once an important route reaching up the north of the Coyles to Loinmuie, a farm-toun that lay half-way to Birkhall.

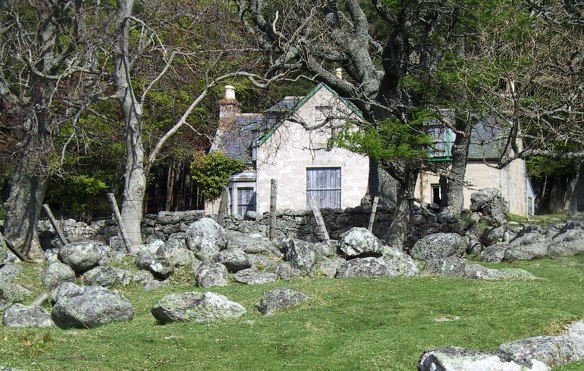

Lynvaig (now known as Loinveg) was the last of the Girnoc farms to empty yet every time I close its gate, winter inclemency has revealed it a little more derelict – this is none truer than with the steading, and old thresher house, which in the winter of 2005 lost their roof after a very heavy snowfall followed by the severest of gales. Yet palpably, despite such attack, it is a farm that oozes a determined will and one that could be brought to work again. But perhaps this is somewhat fanciful as a farm of this size is surely too small to be sustainable in the twenty-first century – and that may be why John Howard Seton Gordon, the current, and 21st Laird of Abergeldy, has given some of the glen away to woodland plantations. The first plantation fills completely the Camlet boundary, but following the recommendations of theCountyArchaeologist, has no tree planting within 10 metres of the ruins. Lynvaig has escaped plantation and so retains its own special ambience, due in part to the tall sentinels of Scots Pine that contrast darkly with the rusty red tin roof of its out-buildings.

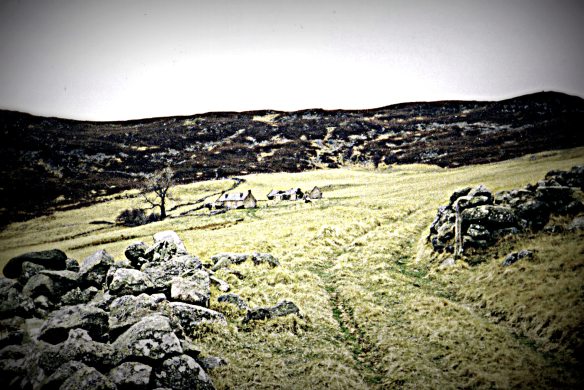

Within 400 yards of Lynvaig, now almost lost in the heather, the first arm, the southern one, of a sweeping track up to The Camlet appears. It is at this point that one fully realizes why the postman used to deliver post to The Camlet on skis! Incredibly an old Austin, belonging to John Jolly, dating from 1935 used to make it up and down this steep, rough and twisting path. The path winds in a double ‘S’ bend through the heather, into bracken and then out into a steep climb on a western slope that has green rabbit grazed grass and stane dykes rising skyward towards the Hill of the Eagle (Sgor an h-lolaire.)

It was on my last visit to the Camlet with my eight year old son Andrew, that we, the Gordon boys, were escorted by a rather special companion, for soaring high over the abandoned farm was a solitary large bird of prey, a Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) perhaps it could not be, but, perhaps you might understand, it was to us! A protectorate for those inextricable souls this bird was truly majestic as its soared, looped and plunged ‘The Camlet’ the capital of the Girnoc. There could be no better home for this bird, favouring as it does remote, wild and open upland moorland. It left me feeling

Today The Camlet is abandoned, like all the Girnoc farms, and gapes utterly forlorn out onto the black massif and patchwork purple grouse-butts of the Coyles of Muick (Hill of the Snakes). In many ways it is a sorrowful sight and nature, as is its right, is relentlessly reclaiming it. Within a decade the Camlet ruins will be lost within an elbow of coniferous forestry plantation. A decade on and surely they will be lost forever. Perhaps that explains a need to bring back to you here the farm-toun in its hey day, when there was up to twenty thakkit-clay biggins with lums reeking merrily, and inhabitants battling the elements with kail soup and illicit liquor as their onlymeans of fortitude!

I shall return you to The Camlet in the next chapter, for it has a cast of stories spanning over four hundred years, and some rather marvelous surprises for all that, but for now it is time to follow that sweeping Camlet road to Bovagli.

Where the curved Camlet track, hugging the contour of Cap na Cuile returns you to the main Girnoc track, there was once a gate. It was at this point that I found, a decade ago, scattered in the heather, the broken letters of ‘The Camlet.’ A sign erected in the 1960’s blown down and iron letters scattered like dust. In that moment I understood that The Camlet was beyond even palliation.

Continuing in that tight curve around Cnap na Cuile one is first greeted to Bovagli by its truly faithful guard – the weathered stumps of its ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and rowan kailyards (Sorbus aucuparia.) These trees are reluctant to abandon their master – and that seems proper. The visitor to Bovagli is struck by the sheer volume of scattered stone, all cast aside, in the long shadow of Lochnagar. The rickles here are everywhere – footprints of two lost farm-touns and their bounded kailyards. Amidst it all is the fading glow of Victorian splendour; a farmhouse of manorial grandeur, but shuttered tight just like every other Girnoc farm. The peeling green woodwork and lifeless cables tell the story. It is hard to believe then that only two decades ago it was a busy working sheep farm as upper Deeside’s most extensive holding of 2000 acres of hill pasture.

Bovagli and Camlet were once truly hand-fast, and as such were more than just neighbours, but compatriots of the Girnoc; tounships, communities, and the life-blood of a small-glen. Their days are now forever past. But in their history there is much to tell: of Bovagli there is its link to HallheadCastle and its most principled farmer, Donald or ‘Auld Prodeegous;’ then there is the lost Manuscript and the poems of ‘Crovie John.’ In The Camlet we have of course Abergeldy, but not just! Cortachy and Airly Castle have a place, as does a distant Priory in Fife. Then there is the auld ‘Minister of The Camlet’ and his zealous and sanctified ways. John Brown, Queen Victoria’s Highland Servant has a maternal place in the history of The Camlet, and the Leys family in particular take the Girnoc back to Glen Gairn. Yes, as you can see, there is much to tell.

The great Strathspey musician, J. Scott Skinner, wrote a tune called Bovaglie’s Plaid, inspired by a local saying that the wood ‘haps, shelters, Bovaglie ferm like a plaid.’ Today the wood is a shadow of its former glory with evergreen aforestation replacing the mixed hardwoods of ancient copses. Leaving Bovagli, past the Dew pond and through the leaning Scots Pines, one takes the main track towards Balmoral. Auld Prodeegous knew this traverse well – his cart passed it daily, whether it was mutton for theQueens larder, or a less than covert trip, to the Inver Inn, for his favourite stoorum!

It was just beyond Bovagli and towards Craig Megen that a Gamekeeper died in a sitting position with his flask at his side, held statue like, with pipe and matches still in his hand. Bovagli’ and her natural powers had reclaimed her own. Bovagli has always been good at that!

Like two broad shoulders the‘Hill of the Eagle’ and ‘The Genechal’ separate the Girnoc from Khantore and the Cabrach. John Robertson (fae the Spittal of Muick) told Ian Murray, who was researching for his book – The Dee from the Far Cairngorms – about a path that used to link Khantore with Bovaglie. They called it the ‘Butchers Walk,’ it was down this track that they carted the best wethers (young sheep) for Queen Victoria’s Mutton Larder. The path is gone now and forestry plantation covers part of it. At The Genechal, the southern end of the Butchers Walk can just be found, as it descends that first shoulder.

The Genechal, like The Camlet was always described thus, preceded by ‘The’ making it a definite article. I was once humourously chastised by Margaret Kennedy the last widow of Camlet; ‘it’s The Camlet ye ken’ she retorted in her doric tongue. The Genechal has a story all of its own, one hard to believe today, as it stands pathetically forlorn, slateless and lost in its wood. The story of its two front doors is beautifully rehearsed in Robert Smith’s A Queen’s Country, but I have discovered much more to that story, so you must read on. The Genechal does have a place in the Girnoc – as it is literally its back door, and was once specially linked to The Camlet by a track known locally as the ‘Skylich.’

It is from The Genechal that you can return to the main track between Inchnabobart and Easter Balmoral. These days the track is well maintained presumably by the Balmoral Estate for the Grouse shooting, indeed just beyond the Genechal there is a mock stag carved in wood, it presents for target practice from the track. The young Princes’, William and Harry, have no doubt practiced here. Follow the track down and theDee valley opens up with the distant turrets of Balmoral castle rising forth. At Builteach there is a cattle grid and deer gate, but to the east, in the direction of Princess Beatrice’s Cairn, and in the cast of Tom a Chuir, one finds the lost community of Wester Tilfogar.

Tilfogar is a much corrupted name so we are fortunate that Adam Watson in his comprehensive ‘The Place Names of Upper Deeside’ was able to explain it’s variation. The name derives from Tulach Chòcaire, which rather charmingly translates as ‘hillock of the cook.’ The Tilfogar farmtowns are listed on the Abergeldy estate map drawn up by John Innes in 1806 (and preserved in a hand coloured canvas on the south wall of Abergeldy Castle’s Great Hall.) On that map they are listed as Dalfouger (Easter & Wester) and draughted as of 28 and 26 acres respectively.

At some point Easter Dalfougar was absorbed into the farm of Buailteach, but whilst Buailteach still thrived, Tilfogar was soon, like so many of its counterparts, no more. These days it is just stones in the heather, only the Chòcaire burn marking out where its stanes once stood.

Tilfogar, like Linquoch, has become forgotten history. In this book I hope to rectify that, for Tilfogar was central to the smuggling system of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. That story will be rehearsed in the last chapter of this book, and whilst it is true that Tilfogar is not strictly Girnoc, it had a key crossover with the small glen that could only leave its omission glaring. Mention has been made of the gloriously bearded Adam Watson, and he surely represents the grandfather of the ‘Deeside Detectives’ a colloquialism that I have coined for a whole array of researchers in love with Upper Deeside, all of whom have made it their lifetime gift to pull old Deeside together in an historical amagam of prose and print. The appendix will contain a dedication to these detectives, without whom many of the stories in this book would have been lost for all time.

I may never have heard of Glen Girnock, but I have certainly heard of Glen Muich, for I am researching my father-in-law’s family history from the other side of the world, and may of his ancestors name Glenmuich as their home (e.g. View Mount in Glenmuich), though whether that is the location Glenmuich or the Parish I cannot yet say.

Best wishes from Australia!

Hi Eric,

Glenmuick is neighbouring glen to the Girnoc and is beautiful. Thanks for getting in touch.

aye Peter

I was born in Girnoc close to 80 years ago when it was a bustling farming aria. I was 1 of 15 pupils in the Girnoc School, I have to report to you many of your statements are un true, you need to put more research before attempting to write a book about Glen Girnoc and Glen Muick.

Hamish K

Dear Hamish,

I am so sorry if I have got so much wrong. I did try my best but fully accept what you say. Would you be able to correct all that I have got wrong. I would like that. My sincere apologies. I hate to think I have got the Girnock so wrong. I did this out of love and for no other reason.

I am quite upset at your comments.

Kindest wishes,

Peter Gordon

Hi Hamish,

I am just a visitor to this site, but I too would love to hear some of your memories and knowledge of this area.

Eric (in Australia)

We visited Camlet today and loved it though bleak on a cold day. The daffodils were out and the gas cooker was still obvious in what was once the kitchen.

It is lovely to read about the Glen , a magic place but no eagles today though we saw a crossbill.

Jo Doake

2/4/19

That is lovely to hear Jo. Thank you for sharing.

aye Peter