Chapter 4 of ‘Deeside Tales’:

Abergeldy has become a dear friend to me and perhaps in another life I would be fortunate enough to be its chatelaine. Yet that is nonsense, I am of humble stock and of the small glen, and long since have I given up seeking the thread of gold.

What is it about Abergeldy that invigorates such a pull? Well that pull was first exerted upon Dr John Malcolm Bulloch at the turn of the last century and it never let go. Bulloch was besotted with the estate and returned to it frequently in his long and busy life – and he even wrote a final piece about Bovaglia on his death bed. It is true to say that without Abergeldy, Dr Bulloch would not have ventured into the mighty House of Gordon. Literally, Abergeldy was the glowing ember of a clan.

“I have an unusual affection for Abergeldy family, in as much as it was with it that the House of Gordon started its tortuous career eight years ago.”

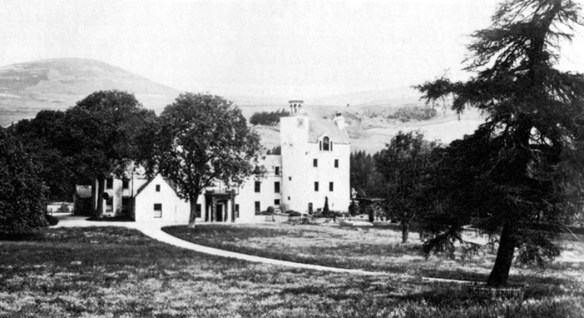

Figure 4.1: Abergeldy Castle in the time of Dr Bulloch

Figure 4.1: Abergeldy Castle in the time of Dr Bulloch

One fact is quite incredible: Abergeldy has the longest single family stewardship of any castle in Scotland – unbroken in nearly 600 years. John Howard Seton Gordon, the genial twenty first laird, continues this family tradition and serves both loyally and true.

“The continuance of these Gordons is remarkable in view of the pressure of their environment, especially in the case of the Farquharsons, who were to a far greater extent the real inhabitants of the district.”

Over the years I have transcribed much of Dr Bulloch’s Abergeldy archive. It was Edward Gordon of Cairnfield who continued Bulloch’s work and whose two million word Gordon manuscript was safely deposited with Aberdeen Special Archives. Cairnfield’s work is truly an unrivalled feat of endurance! In 1925 Reverend Stirton completed his book Crathie and Braemar which contains an evocative and detailed chapter on Abergeldy. Certainly I have absolutely no ambition to present two million words here! Indeed I am rather tired of the genealogical tables that underwrite so much of the landed families. You will have gathered by now, that it is not lists of names that appeal to me, for they are without the stories, the place, and the life; and as such are truly uninteresting. This chapter shall therefore focus on the colourful characters of the Abergeldy family and will strive to place that stewardship in the happenings of the small glen.

This chapter shall also briefly explore the Royal family’s association with Abergeldy which continued with three consecutive forty year leases. In years to come, I envisage that the Royal family will lever Abergeldy out of the clutches of the Gordons. John Howard Seton Gordon, and his wife Gillian, are getting old, and they have no family. On my last visit to them in January 2008, snow had smothered the Abergeldy Park, and the place glistened in the reflected light of Craig nam Ban. That sparkle was soon disowned, as huddled around a 1930’s radiator, inside the windowless vaulted kitchen I found the laird and his wife Gillian. It was a scene as forlorn as it was penniless. Leaving the castle, up the crisp snow covered drive, I felt a true sadness. It pervaded my being for days.

The usual approach, in the review of landed families, is to start with the earliest known generation. However I am not going to be slave to genealogical tradition and will break that ploy. That may be, but to truly understand the Girnoc, the beating heart of Abergeldy, we must return to the early eighteenth century, and introduce Abergeldy’s saviours; Captain Charles Gordon, and his wife Rachel Gordon, tenth of Abergeldy, who to this day, hang in oil portraiture above the fireplace of the Great Hall.

It was my Great Aunt Mabel had who maintained family-lore, that we were ‘off the wrong side of the Abergeldy blanket’ – in other words, that Camlet was an illegitimate son of Abergeldy. The archives indicate that this has something to do with Captain Charles Gordon, who married Rachel Gordon, tenth heiress of Abergeldy in 1698. When this couple arrived on the estate, as newly-weds, it was in absolute tatters. Abergeldy castle had been garrisoned by troops for all of the previous decade and had become the Deeside focus of great disturbance. The castle was ruinous, and the estate, for 15 miles around, had been ransacked and burnt. The scene was desolate. It was Captain Charles and wife Rachel who brought Abergeldy back to any long lost vitality. It was upon this Captain’s coat-tail that many new Gordon families arrived in Deeside: such as those helmed by Nathaniel Gordon of Ardoch (originally from Noth in Rhynie) and Thomas Gordon of Crathienaird (originally from Banff.)

This explains why the early eighteenth century saw the Gordon clan proliferate in giant rippling circles from Abergeldy. The Gordons, it must be stated, were not popular in upper Deeside, especially with their counterparts the Farquharsons & Browns, indeed they were always to be regarded as in-comers! Michie, in his Deeside Tales made no attempt to hide this long-felt district animosity. Yet today, the irony presents itself, that John Howard Seton Gordon, the current and twenty first laird, carries that family record of 600 hundred years unbroken stewardship.

So it was that the Gordons came to dominate the glens – particularly Glen Muick and Glen Girnoc, but also to a lesser extent, Glen Gairn. The parable of the old fairy–tale: the Magic Cooking Pot describes all. Captain Charles brought with him to Deeside several Magic Porridge Pots: “cook little pot, cook!” and they did just that. Of all the glens the Girnoc was the most notorious – and from it, that porridge flowed stolidly thick. So much so that Deesiders of the day were to remark for any puzzle “that’s as inextricable as the sibness o’ the Gordons o’ Girnoc!”

It was many years ago that I first wrote to John Howard Seton Gordon. After that he became a friend. It was obvious to me, from our early conversations, that the laird was a man who devoted himself to his estate and to the tip top husbandry of his farm. Many years passed by and life moved on. Fatherhood came again and cast its unrivalled joy; for nothing, absolutely nothing, can beat the joy of that. This time, to join the brightness of my son Andrew, was the radiance of Rachel.

A few more years passed, and as befits the un-retiring, dreamy thoughts drifted back to Deeside. It was then that I recalled the laird telling me of the painting of Rachel hanging above the fireplace of the Great Hall. Curiosity began to stir. It must be said that we had not chosen my daughter’s name because of Abergeldy – rather because it was a name that enveloped the beauty of her being.

It was this curiosity about Rachel that brought about a summer invitation to the castle. This visit was recorded by me in my diary:

“It was Andrew, the magical Andrew, that was to be the star for the laird. Halle-Bop was indeed to shine bright over Abergeldy that night. For Andrew, age seven, Abergeldy and its castle was about to come alive. And for the laird one could truly sense the rising vapour of his lost youthful vigour – a child in his castle and a chance to make it magical – that is what he would do – and that is what he did.

The Great Hall was intimate – not as I had imagined. It was more beautiful. It had a vaulted roof, limed and painted walls, and two large south facing windows that, on the day we visited, allowed beams of sun to lighten it magically. The light caught the dust and cast hazy clouds – particles dancing as if in delight: ‘visitors at last…visitors at last.’

Above the fireplace was a plaster painted and gilted crest – the crest of the Abergeldy Gordons with the motto “God With Us” The laird explained it had originally been on the ceiling. Either side hung two oil paintings in gilt frame. To the left was Rachel Gordon the 10th heiress of Abergeldy and to the right Captain Charles Gordon her husband. It was fitting that they sat so prominently for it was this couple that restored the estate for the family, and brought renewed life to upper Deeside. In 1715 they completed the build of Birkhall and it was Rachel and Charles who restored Abergeldy Castle to its former glory.”

Figure 4.4: Abergeldy’s Great Hall

Figure 4.4: Abergeldy’s Great Hall

The laird was a wonderful host that day but was sad not to see little Rachel. ‘One day perhaps’ he said, ‘you will bring little Rachel to me.’

Like a defining mark, Rachel Gordon, separated two distinct chapters in the life of the estate: pre- and post-Rachel. Had she not married Captain Charles Gordon of Minmore the family seat would have been broken.

The plan for this chapter is to start first with Rachel’s story and then step back in time to the more interesting of her early forebears. This whole exercise is difficult for there is much to include that is of interest and the generations that follow Rachel are just as crammed with incident. The aim is not to be inclusive – if you want a comprehensive account I would respectfully suggest you return to the work of Dr Bulloch and his Abergeldy Monograph (and other associated manuscripts – listed in the Appendix.) The transcribed work, in fact my whole Deeside archive, will ultimately be left alongside Bulloch, in Aberdeen University’s Special Archives.

Figure 4.5: Abergeldy from the air (RCAHMS image)

Figure 4.5: Abergeldy from the air (RCAHMS image)

Abergeldy, the name, is derived from ‘abhir gile’ or confluence of the clear stream, and lies on the south bank of the Dee, some six miles by road west of Ballater, and one and a half miles east of Crathie Church. The castle is cradled in the very footprint of Creag nan Bam, and on the north side, by the farm of Torgalter. These days the castle is hard to spot as the wood around it has grown so much that its pink rendering, clock tower, and cupula, are barely visible from the road. The white footbridge to the castle is just as hidden, and lies rusty and padlocked; forlorn in its neglect.

In researching Abergeldy I was left to muse over its derivation: the confluence of the clear stream: in many ways this seems apt for the Gordon family. This was a family of clear thinkers not sportsman, a family who used intellect over guile, wisdom over instinct. There was no great good, no national cause, but there was a true humanity, generosity and passion. The Farquharsons may still have had the upper hand in the district – but the Gordons had those characteristic genteel features nursed by admirable purpose.

As early as 1378 Abergeldy was described as one of the Aberdeenshire castles ‘of most respect’ and was accordingly fortified and equipped with a moat, which together with the river, gave it an almost island site. Its position beside the Geldie confluence, was strategic indeed, and had always been the fording-point in the river Dee, southwards to the hills of Angus. The moat has now long since vanished, and inevitably the house has suffered, but ever steadfast, the Keep has survived as an original tower-house.

The sheer antiquity of Abergeldy can be measured by a large standing-stone monolith on the riverside lawns; clearly Stone Age man had seen the advantage of the site. These days this icon is lost in over-grown garden shrubs and a mixed plantation of ornate trees. At one time Abergeldy had a truly ancient Larch tree that was the envy of the district. The Larch (Larix decidua) with its soft and bewitchingly delicate green, is my favourite conifer, especially when grown as a specimen tree. Apparently one of the Lairds of Invercauld asked the Laird of Abergeldy how he came by such a fine larch tree outstripping his own in size. The reply came, ‘It’s just ane o’ yours, Invercauld, that I put in ma pouch lang sine!’

Figure 4.6: Abergeldy in 1871 with its standing stone and Invercauld Larch

Figure 4.6: Abergeldy in 1871 with its standing stone and Invercauld Larch

Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort, once established at Balmoral, wished to buy Abergeldy, but the Gordons would not sell. In his book, Balmoral: The History of a Home, Ivor Brown gives a rather benign view of the Royals which my research would refute: ‘Royalty, at least during recent years, has not had these powers of Seizure, and would be too humane to use them if it had.’ In 1878 The Queen bought Ballochbuie Forest – the ‘Bonniest Plaid in Scotland’ from the Farquharsons for £100,000, but the Gordons, in defiance, were only prepared to lease their castle and estate.

The Abergeldy property was at one time an extensive one, extending on the south to the White Mounth (Lochnagar), eastwards to Glenmuick, where it included Strathgirnoc and Stering or Birkhall, and west and south-westward, to Glencallater. Much of the estate consisted of no more than moor and rough pasture, and as such, apart from its best farms lying along the Dee, it offered poorish returns. In 1696 the lands in Crathie parish were valued at £600, in Glengairn at £140, and in Glenmuick £430.

Figure 4.7: Abergeldy Castle as it is today

Figure 4.7: Abergeldy Castle as it is today

The Castle has been much altered and added to, but still retains the original tower which formed the nucleus of the whole, and which, with its rounded angles, crow-stepped gables and somewhat elaborately corbelled angle turret, is a good example of the 16th century manor house. The West wing which was an extensive assemblage, largely of the Royal family, has now gone. The current and twenty first laird, found that the building was ravaged by dry-rot. The repair cost was exorbitant and beyond his means and so he had it demolished in 1967. So today we are left with the original tower-house, lime rendered and pink, and crested by its cupula. In some ways it is a strange combination, but it is rather endearing for it.

Figure 4.8: The Abergeldy kitchen served a ginormous appetite

Figure 4.8: The Abergeldy kitchen served a ginormous appetite

When, in 1902, Dr Bulloch was writing his monograph there was much heightened interest in Abergeldy because of the Royal lease which had continued from 1849 with both King Edward VII, and King George V, having occupied it when Prince of Wales. It is recorded that the rent of Abergeldy in the early years of the twentieth century was £4500 a year. Before that time Queen Victoria rented the castle for her mother the Duchess of Kent. Within the Abergeldy walls Edward Prince of Wales must have truly feasted, with his renowned gigantean appetite, satisfied by five meals per day. Indeed I nearly fell of my bench laughing when I came across a lost picture of the Abergeldy ovens for truly they were necessarily large for the appetite of a King! It seems likely, that it was his son George (later King George V) that had the external Abergeldy tower clock assembled and installed; for you may recall that he had an obsession with time-keeping that cast pedantic discipline over his whole life and that of his family! Certainly the clock at Abergeldy, seems to me, otherwise incongruous.

“The Prince of Wales liked to be outdoors as much as possible and he devised the idea of ST – Sandringham Time. The idea was to make the most of the winter daylight hours for his passion for shooting and so the clocks all over the Sandringham Estate were advanced by half an hour. King George V maintained this custom during his lifetime.”

Figure 4.9: Both King Edward VII and King George V stayed at Abergeldy when Prince of Wales

Figure 4.9: Both King Edward VII and King George V stayed at Abergeldy when Prince of Wales

Birkhall, with an estate of 6,500 acres was bought from the Gordons by Albert the Queen’s Consort. He gave the property to his son, Edward Prince of Wales, but Queen Victoria claimed it back in 1885. The Abergeldy rumour has long whispered that the Laird lost Birkhall in a card game! After his marriage in 1863, Edward Prince of Wales stayed every year at Abergeldy Castle, and there made holiday with shooting by day and cards by night. In 1871 he asked Mr Gladstone to drive over from Balmoral to dine. Gladstone was charmed by the Prince’s manner, but not so happy about his morals, at least in the small matter of gaming. I was saddened that the entry in Gladstone’s diary does not record who won the card game at Abergeldy – or how much!

It is rather amusing to think that Birkhall, rumoured, lost in a game of cards, became the setting for six Royal honeymoons. Such is fate!

Figure 4.10: Birkhall, it has been rumoured, was lost in a game of cards!

Figure 4.10: Birkhall, it has been rumoured, was lost in a game of cards!

Today the tourist has long since forgotten this historic Royal association with Abergeldy, though there is greater appreciation that Birkhall (Abergeldy’s offshoot) is the true highland home of Prince Charles the current Prince of Wales.

Birkhall brings us to Rachel Gordon.

Mystery surrounds the period of time in which Rachel Gordon became Tenth of Abergeldy. We know that she married before March 1690 Captain Charles Gordon of the 1st Regiment of Scots Foot Guards for at the beginning of that month there is a charter of resignation by her as his spouse of the land of Abergeldy. This is intriguing as her only brother John (the ninth laird) was still alive at this time and lived for another eight years. This charter was lost in a fire in 1812 and thus we are left to speculate. One assumes that Rachel signed only her rightful share of Abergeldy to her new spouse unless, for some reason or other, her father had left the whole Abergeldy estate to her instead of to her brother.

As a historian I have absolutely no time for conspiracies but do have an innate feeling of trouble relating to this Abergeldy juncture. John Gordon the ninth laird, and older brother to Rachel, has you see absolutely no archival presence. He lurks as the most ghostly of figures and then simply disappears.

John Gordon, the ninth laird, married Elizabeth Rose, daughter of (the late) Hugh Rose, XIV of Kilravock. The marriage contract of December 1694, was witnessed at Kilravock by, amongst others, Captain Charles Gordon in Pitchaise. Elizabeth Rose followed her vows by entering a marital agreement which she signed as Betty Rose in a ‘sweet Roman hand.’ Her brother, Kilravock, instantly made payment of 7,000 merks in name of a tocher, and instructed that Betsy is to be “infeft in 1,400 merks of yearly rent out of ye barony of Abergeldy, and to have the manor house of Abergeldy to live in if she becomes a widow during the life of Euphemia, Abergeldy’s mother, and after Euphemia’s death to have the house of Knock as a dowery house.”

It is then recorded, withoutfurther detail, that in 1698, four years after his marriage, John Gordon the ninth laird, died without leaving issue. He was the last of the ‘Seton’ Gordons but was succeeded by his sister Rachel. It has to be important that this instrumental period in Abergeldy was set amidst the strife of national religious unrest which escalated up to the abdication of James II of England and VII of Scots on 11th December 1688

James II of England and VII of Scotland (1633–1701) was the last Roman Catholic monarch to reign. Religious tension intensified from 1686: James controversially allowed Roman Catholics to occupy the highest offices of the Kingdom and received at his court the papal nuncio, the first representative from Rome to London since the reign of Mary I. Many of James’ subjects distrusted his religious policies and despotism, leading a group of them to depose him in the Glorious Revolution. He was replaced not by his Roman Catholic son, James Francis Edward, but by his Protestant daughter and son-in-law, Mary II and William III, who became joint rulers in 1689.

The belief that James—not William III or Mary II—was the legitimate ruler became known as Jacobitism (from Jacobus or Iacobus, Latin for James). James made one serious attempt to recover his throne, when he landed in Ireland in 1689. After his defeat at the Battle of the Boyne in the summer of 1690, he returned to France, living out the rest of his life under the protection of King Louis XIV.

Adherents of the deposed King James II, led by John Graham, Viscount Dundee, now began to take up arms against the new regime of King William and Queen Mary.

The leader of the Government forces, supporting the cause of King William and Queen Mary, was General Hugh Mackay. Born in 1640, he was the third son of Colonel Hugh Mackay of Scourie in Sutherlandshire, and like Viscount Dundee, had for some years been serving with various regiments in Europe. In January 1689 Mackay, now elevated to Major-General by William, Prince of Orange, was in command of the British regiments who supported William. As Major-General of all the forces in Scotland, General Mackay now faced the task of subduing the unrest which Viscount Dundee was advocating.

The deposed King James’ son James Francis Edward Stuart (The Old Pretender) and his grandson Charles Edward Stuart (The Young Pretender and Bonnie Prince Charlie) attempted to restore the Jacobite line after James’s death, but failed.

All this unrest was to affect Abergeldy, and occurred in the period when John Gordon succeeded as the ninth laird. It was clear that John Gordon the Abergeldy laird had catholic leanings and supported the deposed catholic King. John apparently survived the difficult times without arrest as it was recorded in the Balbithan Manuscript that he did not die until 1698 and he was to appear in the Poll Book of 1696 as follows:-

1696: John Gordon, Laird of Abergeldy, Crathie, Mrs. Bettie Ross (Rose) his lady.

Shortly before John Gordon the ninth laird of Abergeldy’s succession, General Mackay had set out to arrest Viscount Dundee who had declared for James II & VII. Dundee escaped to Glen Ogilvy thence to Braemar where he was protected by John Farquharson of Inverey ‘The Black Colonel.’ As Inverey house was very small, Dundee transferred to the stronghold of Abergeldy and from there organized his forces. After Dundee had left the district, Mackay advanced there, ‘and harried the country for 12 miles around Abergeldy destroying 1400 houses.’ Mackay burned Inverey and then descended on Abergeldy, the castle of which he garrisoned with 72 of his soldiers.

‘By November, 1689 General Mackay’s troops had over-run the area around Braemar and Abergeldy burning the land for twelve miles around including a large number of crofts on the estates, the official estimate being one thousand four hundred dwellings. General Mackay garrisoned seventy two of his soldiers in Abergeldy Castle to keep watch on the activities of the Farquharson Clan.’

It is most surprising to learn the name of the officer in charge of the garrison of soldiers who had overrun the Abergeldy Estate and occupied its Castle – it was none other than Captain Charles Gordon of Pitchaise. His sympathies were clearly protestant and his actions targeted directly against his brother-in-law John. Captain Charles had been a member of ‘Lauder’s Troop.’ Lieutenant-colonel Lauder, with his party of two hundred elite troops were with General Mackay at the Battle of Killiecrankie in July 1689, and were one of the first to escape from the carnage.

Viscount Dundee was killed in the moment of his victory, at the Battle of Killiecrankie in July 1689, destroying all hope of returning King James II of England and VII of Scotland to the throne. The death of Viscount Dundee saw the end of the Jacobite campaign and it fizzled out after losing the battle of Dunkeld in August 1689.

General Hugh Mackay who had been so badly routed at Killiecrankie and, but for the death of Viscount Dundee on the field of battle, the whole future of Scotland may have been dramatically changed, was himself killed at the Battle of Steenkirk in August 1692, fighting in Europe for King William III.

Most frustratingly, the life of Abergeldy, amidst this pivotal time, was lost in the charter chest fire of 1812. That is a true shame, for this escapade, suspended in such religious unrest, reeks of family divide. I have wondered if it was this ‘divide’ that ultimately brought an end to John Gordon, the last Seton laird of Abergeldy? However a list of Ten Commandments by General Mackay has survived, and what stands out is the ruthless rigour of the grim destruction to upper Deeside. The small glen in particular, the beating heart of Abergeldy, would have suffered badly. The Camlet and Bovaglia were ransacked and burnt, and their cottertowns laid to ruin. The small glen had not escaped the dire imposition of national religious divide!

The INSTRUCTIONS given by General Mackay to Captain Charles Gordon while in occupation of Abergeldy which have been preserved in the Abergeldy Charter Chest may be read as follows:

1. Furnish the garrison with corn, cattle and sheep to be taken without ‘tack’ or payment and terrify the country with parties while the enemy were about.

2. Burn the houses and crops of such as would not come in and give up arms and houses where arms might be found.

3. Protect those that delivered up their arms and took the oath of allegiance.

4. Correspond with the master of Forbes, taking direction from him and advising him of what he might need.

5. Take the nearest corn from those in rebellion to repair what damage his mother-in-law had received and destroy and burn the rest unless submission was made.

6. So behave only in the influence of the service that no accusation could be brought against him in following any relation on the opposite side.

7. Burn the district of Braemar, but wait until he could do safely.

8. Do his best to capture or kill Farquharson of Inverey in which event the General would intrude for the interest of the latter’s children, nephews of Charles, and would lead to Charles own preferment.

9. Obtain witnesses against the Laird of Abergeldy (John) to prove that he had joined the rebels in Arms which case Abergeldy would be secured for John’s sister, wife of Charles.

10. Treat Farquharson of Monaltrie and his tenants with the same rigour as the rest, it being apparent that the tenants have been in arms and Monaltrie a hypocritical loaming conniving of their perjury and rebellion.

For Rachel Gordon what an eventful decade the last of the seventeenth century had been. This decade had started with her marriage to Captain Charles, who was in command of the Garrison that was close to seeing an end to Abergeldy destroying, burning and pillaging all around. At the same period of time her brother John was cited for his Jacobite sympathies, but appears to have survived both arrest and hostilities. In 1698 John died and Rachel became rightful heir. This was a pivotal hour in the Abergeldy calendar and nobody could have predicted what was next to come.

Captain Charles Gordon and his soldiers seem to have stayed at Abergeldy for quite some time and no wonder the castle was in a ruinous condition in 1732 as noted by Sir Samuel Forbes.

You will see from the above that General MacKay specifically commanded Captain Charles to ‘Do his best to capture or kill Farquharson of Inverey.’ Also known as ‘The Black Colonel’, John Farquharson of Inverey was a violent man in a violent age. Outlawed in 1666 for the murder of a Ballater laird, he became a hunted man, but nevertheless spent much time in his own castle of Inverey, and fought at the battles of Bothwell Bridge and Killiecrankie. Cornered on one occasion by redcoats in the Pass of Ballater, he ensured his own immortality by escaping on horseback up the near precipitous north side of the defile. Eventually a redcoat ambush was laid for him at Inverey, but forewarned, he escaped, and watched his castle burning. He thereafter took refuge in the ‘Colonel’s Bed’, below a rock overhang in a gorge in the River Ey, where his light o’ love, Annie Ban brought him food. Before he died, about 1698, he instructed that he was to be buried at Inverey, beside Annie Ban, but for some reason he was instead buried at Braemar. The next morning, his coffin was found on the ground beside his grave, and was re-buried. On the third occasion this happened, the coffin was taken to Inverey for re-burial, and was heard of no more.

The ransacked Abergeldy estate was, despite such terrible destruction, still of value, as delineated in the 1696 Poll Book where it was valued for Glenmuick as £430 out of the total of £1,122. Who was it that had the energy, drive, and finance, to restore such a forlorn concern? Indeed Abergeldy’s future looked dismal and many feared the end of the Gordon estate. The knight in shining armour that came to Abergeldy’s rescue, hinted to above, and presenting perhaps the greatest of ironic twists, was none other than Captain Charles Gordon of Pitchaise.

Pitchaise was no bedfellow of Abergeldy and how it came about that Rachel met Captain Charles is simply unknown. Pitchaise was a small estate, far away from Deeside, on the southern bank of the Spey River belonging to the Grants. In the same Strathaven district was Captain Charles Gordon’s family of Minmore.

Captain Charles Gordon belonged, through his father, to the Gordon family of ‘Jock’ Gordon of Scurdargue, and through his mother, Janet Gordon, (daughter of Sir Alexander Gordon, 4th of Cluny) to the Ducal Gordon line. So he had an interest in both Gordon lines and as a relative, could mix readily with either side of his Gordon family.

Figure 4.13: Captain Charles Gordon

Figure 4.13: Captain Charles Gordon

Sir Alexander Gordon, 4th of Cluny, the maternal grand-father of Captain Charles Gordon needs mention here. He was a man who bowed to no-one except his King and Chief, to both of whom he was related. He seems to have been continually in debt, even facing imprisonment in 1630 when he was forced to sell some of his lands to satisfy his creditors. Although he had debts amounting to 39,000 merks in 1633 he still had duty of tour, first to England and then on to Europe on business for King Charles I, not returning to Scotland until 1638. As an ardent Royalist supporter in the years leading up to the Civil War he brought to Aberdeen a large shipment of ‘arms, muskets, pikes and other weapons.’

The remaining years of Sir Alexander Gordon were spent as he had always lived, full of excitement, intrigue and danger. One opponent at the time described him as, ‘ane incendiarie and mane informer of the Marquis of Huntlie.’ Because of his political leanings, Sir Alexander Gordon spent some time in confinement, until released by the Earl of Montrose in August 1645, after what was Montrose’s last Royalist victory at Kilsyth. Sir Alexander Gordon, 4th of Cluny died the following year in November 1646.

Captain Charles inherited his grandfather’s dynamism and purpose. After those ill years, a curious twist of fate had returned him to Abergeldy, and to the very castle he had once garrisoned. From 1698, Captain Charles and his young wife Rachel brought a new regime to Abergeldy, and a steely determination to right a wrong. Not so many years before, under the orders of General Mackay, he had sent out his troops from the castle to pillage, ransack and burn ’12 miles around.’

One researcher has described Captain Charles in somewhat prosaic terms as having ‘swept into’ Abergeldy from Pitchaise in 1698 ‘like a breath of fresh air.’ However surely there must have been much uncertainty about his arrival. It is my belief that the Girnoc folk must have been fearful of Captain Charles, as not so many years before they had seen his troops overrun and lay-to-waste their farm land, scatter their cattle, and destroy completely their crofts. However such fears were not to be borne-out. Captain Charles had, by the inheritance of his wife Rachel, been given an opportunity to put it all back in order again. That was how, on the threshold of a new century, a whole new community was started on the Abergeldy estate.

What Captain Charles Gordon needed most in 1698, was money and skilled workers. He required a reliable workforce for his projects, who could help him re-establish the Abergeldy estate; labourers, artisans, stone-masons and journeymen and loyal tenants who would be rewarded eventually, with grants of land and crofts. He started by re-establishing the Abergeldy farms and building the House of Birkhall on a small estate which had formerly been called Stering in Glenmuick. It has never been recorded before, but has become clear to me, through years of detailed research, that this workforce came principally from Strathdon, and in particular, from Glenbuchat.

There is some uncertainty but it seems likely that Rachel’s mother Euphemia Graham was still going strong at the seventeenth century’s turn and that she occupied Knock castle. Abergeldy castle itself was ruinous and so what became of ‘sweet’ Bessy Rose, the childless widow of John Gordon, the ninth laird, is unknown. She had brilliance for sure, but was probably swept aside by her energetic brother-in-law.

Figure 4.14: Birkhall as it was in the eighteenth century. The house built by Rachel in 1715

Figure 4.14: Birkhall as it was in the eighteenth century. The house built by Rachel in 1715

In 1700, Charles Gordon signed a bond for the Earl of Aboyne insuring the peace of the country. He seems to have retired from active service late in 1703 or early 1704 for, in the latter year he was made a Commissioner of Supply. Charles Gordon was described by Dr Bulloch as a ‘capable man of affairs’ and was appointed arbiter in local disputes. In November 1705 he was in Edinburgh on some such business for Lord Mar when his wife Rachel wrote to him from Abergeldy:

“I shall wish ye make all haste to come home ye can. Your children are blessed be God in good health. Wishing the Lord may be with you, and restore you and those in company with you to your own again, grant us a happy meeting.

I am, my dearest, your most affectionate spouse.

P.S. My dear, with all the trouble you have, buy me an apron of coloured Irish (Highland) tartan or calico.”

Charles Gordon had a dispute of his own in the matter of grazing rights with the Earl of Aboyne as superior of the forest of Breckach which belonged to the Earl, all except such parts held in ‘feu ferme’ by the Lairds of Abergeldy as sheilings and grazings, a dispute which had been going on for a considerable time, as shown by the following document written after 1702:

“This totall subversion of the ordinary use of this said wholl forest and shealings both by superior and vassals into a grasing for low country cattol did not exterpat the King’s deer and utterly ruin the poor country round it for want of the usuall pasturages for their proper crofts, but created such animosities and misunderstandings betwixt them, particularly betwixt, Charles, Earl of Aboyne, the present Earoll his grandson, and Alexander Gordon, then of Abergeldy, and John Gordon then of Braichlie, that what by processes, dryrings, law borrows, and other mutual acts of bad neighbourhood, they was all put to considerable charges and troubles and were never reconciled, or that affair anyways adjusted loam the day of all their deaths.

Therefore what, by reason of the Late Earl Charles, his minoritie, the revolution and army about that time a praye to all grazing cattoll, the late John Gordon of Braichlie going wrong in the head, and imprisonment, and consequently incapable of looking after any business, and then the monage and death of the late John Gordon of Abergeldy, things stood much as they were without any noticeable occurrence or variation until after the death of the late Errol (who died in 1702) that arose a fresh process put upon the old score of grazing upon Glengusachin betwixt the present Earll’s tutor and the present Charles Gordon of Abergeldy, which yet depends and has already stood the family an hundred pounds sterling of charges which will be clearly seen by the tutor and his factor’s accounts, although come to no issue to this day.”

You can glean from the above that it was Rachel’s father Alexander Gordon and John Gordon of Braichlie who had first disputed with the Earl of Aboyne over grazing rights. So acrimonious was the fall out that legal proceedings continued over two decades – such were the ‘mutual acts of bad neighbourhood.’

Captain Charles brought several Gordon cadets to Deeside and two families in particular stand out. The first is the Gordon family of Crathienaird who were to be of some standing in the district and indeed were Executors representative for Abergeldy. It has been convincingly argued that this Crathienaird family came to Deeside from Letterfourie in Buckie. The progenitor was Thomas Gordon of Myreton who married Anna Hamilton. Their son Thomas Gordon is the proposed first of Crathienaird. Their daughter Mary is also of much interest for she married (probably in the same year as Captain Charles) Nathaniel Gordon of New Noth in Strathbogie.

New Noth and Abergeldy have a special hand-fist bond of that there can be no doubt. Captain Charles’ brother Alexander of Glengarroch inherited half of New Noth in a charter of 1667. The estate was shared with Nathaniel Gordon

Nathaniel Gordon of New Noth (c1646–1721) was well-to-do and prosperous. He was Chamberlain to the Marquis of Huntly from 1690 till 1699 during the time of the Marquis’ wanderings in Europe, practically an exile after the Revolution of 1689. As his Chamberlain, Nathaniel Gordon had charge of the Marquis’ domestic affairs in Scotland.

Nathaniel Gordon lived at Noth with his wife Mary and her family. This included Thomas Gordon (his sister’s brother) who was later to be first of Crathienaird. The family appear in the 1696 Poll Book for Rhynie parish as follows:

Nathaniell Gordon, gentleman, Newnoth, Rhynie, and his wife, and Anna and Jean his children; Agnes Hamilton, his mother-in-law; Thomas (Gordon) her son

Nathaniel Gordon gave up New Noth in 1714 and went to Deeside where he lived at Ardoch with his wife, Mary Gordon and one of his daughters. Ardoch was neighbour to Crathienaird. It seems highly likely that Nathaniel’s relocation from Rhynie to upper Deeside was related to the historical events which began to develop in August 1714 with the death of Queen Anne; and the proclamation of George, Elector of Hanover as King George I

History tells us about the ‘Hunting Party’ of interested persons, meeting in Braemar and arranged by John (Erskine) Earl of Mar; the formulation of plans for an Uprising, made at Lord Gordon’s Aboyne Castle; and the defining act, the Standard raised at Castletown of Braemar on the 6th of September 1715 for King James VIII, who became known as the ‘Old Pretender.’ It is reasonable to suppose, that Nathaniel Gordon was involved in some capacity, in these momentous events.

Nathaniel Gordon died November 1721, at Ardoch. He left a widow, Mary Gordon and two daughters, Anna Gordon and Jean Gordon. Although Nathaniel apparently left no male heir – the name Nathaniel Gordon continued in upper Deeside, at both Toum in Glen Gairn and at Wardhead in Glen Muick. The latter has been claimed as the progenitor of The Camlet.

There is a fascinating account relating to Drumel stone which is to be found at New Noth. In 1823 this stone was dug up and moved about 20 feet. At a depth of 3 or 4 feet under an urn was found containing ashes, a piece of tartan too decomposed to be identified, and copper and silver coins dating from the reign of Mary Queen of Scots. The urn was reburied in situ.

Mrs Kathleen Davidson remembers the Drumel stone of New Noth from the early twentieth century:

‘Sixty years ago I used to go for holidays in Aberdeenshire with my grandparents. Grandfather was a shepherd in the Glen O’ Noth, Gartly. There was an old stone standing in a field on New Noth Farm which I passed every day when going for milk. It was supposed to mark the grave of an old warrior. The story I was told was that one year they were building a new cow house and took the stone to use as a lintel. The first night after the cows were shut in, they made a great rumpus. The farmer and my grandfather went out the next night to stand guard with guns. They never told what they heard or saw, but the stone was taken out and put back in the field.’

Let us now leave New Noth and return to Deeside. Though placed by Alistair and Henrietta Taylor among the Jacobites of 1715, Captain Charles Gordon does not appear to have taken any active part in the rising, and indeed was opposed to it as appears from a letter of the 1st of September to Lord Polwarth in the Marchmont M.S. –

“Upon Friday last the Lairds of Invercauld and Abergeldy deserted and went off from the Earl of Mar.”

His connection with the latter no doubt accounts for his presence at the Aboyne Castle meeting two days later, but he was not admitted to the council of leaders and was so far distrusted that a guard was placed over him.

Captain Charles Gordon and Rachel, tenth of Abergeldy had three children: Peter, Alexander and Joseph. Shortly we shall return to Peter the eldest child who succeeded his father as eleventh laird of Abergeldy, however it is worth briefly portraying the lives of his brothers Alexander and Joseph.

Alexander Gordon chose to live at the head of Glenmuick at Aldihash (Altnagusach). He was educated at the Grammar School, Aberdeen and was at Marischal College between 1706 and 1710. He went on to become a successful Advocate and Merchant in Aberdeen and acted as a tutor and guardian for his nephew, Charles Gordon (the twelfth Laird.) One of Alexander’s servants, Charles Davidson, was imprisoned at Aberdeen for taking part in the rebellion of 1745.

Alexander died at Aldihash in November of 1751 he had just entered his sixtieth year. His nephew Charles Gordon of Abergeldy was his executor dative qua creditor. Charles had paid over £165 for his grave linen, coffin and funeral expenses; and £36 to a physician “for his pains and trouble in coming about 18 miles and attending the defunct during his sickness whereof he died.” The inventory contains the sum of £225.8s Scots, as the value of his household furniture, cow, calf, an old horse and other effects, rouped on Christmas Eve 1751, by Samuel Gordon in Milltown of Braickley and Charles Farquharson in Drumnapark, Joseph Gordon in Birkhall being judge of the roup.

For sometime I have wondered why Alexander, a successful Advocate and Merchant in Aberdeen, chose remote Aldihash as his home. It was, in his time, a humble farm-toun and had apparently no signs of outward prosperity; the itinerary of his death roup would apparently confirm this.

Figure 4.15: Aldihash ‘The Hut’ as it was in 1806

Figure 4.15: Aldihash ‘The Hut’ as it was in 1806

However Aldihash has forever remained dear to Abergeldy’s heart, and from the late eighteenth century onwards, served as a favourite refuge for shooting parties. A small cottage was specially built for the purpose with a shelter of deciduous Larch trees (Larix spp) to protect from the cold Lochnagar sweep. It was at this time that Aldihash became affectionately known as ‘The Hut.’ Alexander’s old home was renowned for its beautiful setting, its clarity of air, and its peaceful ambience. Autumn shooting parties were lavish affairs, and over the years, the Hut was expanded to provide greater servant accommodation. Aldihash was a spot where the eagle was frequently sighted. Queen Victoria and her family regarded ‘The Hut’ with special affection. Alltnaguibhaich – the burn of the fir tree, was a favourite picnic place. However, after Albert died Queen Victoria built the Glasallt Shiel and frequented that instead.

Perhaps then we can understand genteel Alexander. He had seen the beauty and serenity of remote Aldihash, and had watched the eagle soar its heights. He was in love with a home completely removed from frenetic Aberdeen. It is heart-warming to think that the warm glow Alexander felt for Aldihash was to live on in the heart of Abergeldy and was to envelop even Queen Victoria herself.

Figure 4.16: The Hut at Aldihash

Figure 4.16: The Hut at Aldihash

Joseph Gordon was the youngest child of Captain Charles and Rachel Gordon. Whilst his brother Peter inherited Abergeldy, he was left the family home of Birkhall, built by his parents in 1715. Over the entrance lintel to Birkhall, a typical, but now much extended Ha’ House of the period, is the inscription 17 CG RG 15.

Joseph Gordon has long since captured my fascination. Some years back Joseph was introduced to me by letter as ‘the mysterious and shadowy Joseph.’ No researcher to date has managed to reveal the life behind Joseph and it is indeed unlikely that they ever will.

What then do we know? Well apparently Joseph liked to be known as ‘The Judge.’ He had it seems a touch of auld Prodeegous! It is also clear that Joseph loved his Deeside estate and was living at Birkhall with his wife in November 1735 (when he acted as Executor to his deceased brother Peter) and was still there in December 1751 (when he rouped his deceased brother Alexander’s effects.) Joseph married in 1734 Elizabeth Gordon, daughter of James Gordon of Tilliefour. Her family descended from the Terpersie Gordons (the Terpersie castle seat is at the heart of the Correen hills about three and a half miles north west of Alford – it is now ruinous.) The ladies of the Terpersie family were renowned for their beauty and stature. The contract of marriage between Joseph and Elizabeth outlines vast prosperity, with each bringing more than 5000 merks to the bond, and securing it for their future children. Together, it is documented that they had a ‘family of six’ but we only know of three children; Charles, Alexander and David.

Nobody has ever recorded the death date for Joseph, but I am inclined to believe that it may have been as late as 1768. To understand this you must understand that there was an unexplained thirty-one year delay in serving heir to Joseph’s nephew Charles. Aged 15 years (or there-about) Charles was served heir in 1737 to his father Peter Gordon the eleventh laird. However he was not served heir to his grandfather Captain Charles, well not in 1737. Indeed, and most curiously, he had to wait until 1768 to be served heir to his long dead grandfather. It is my belief that Joseph retained title to Birkhall up until this, his date of death.

There is reason for all this detail. Some years back speculation arose whether the Camlet Gordons were sired by the ‘mysterious and shadowy’ Joseph of Birkhall. You may recall that Camlet John had a brother called Joseph and also called his first son Joseph. The fanciful muse was that Joseph Gordon of Birkhall, an ardent Jacobite, was in hiding in the small glen after the 45’ rebellion. In order to avoid forfeiture of his estate his hiding had to be absolute and any children born in this period might well have been hidden. Could two of these children have been none other than Camlet John and Camlet Joseph? This is a theory that I now think unlikely but not impossible.

It was Joseph Gordon’s wife Elizabeth who sheltered the Oliphants of Gask, when the latter were in hiding after Culloden. Joseph was by then already in hiding himself. Elizabeth had reason to support the catholic claim to the throne as her father James Gordon of Tillyfour was killed in the 1715 uprising. Elizabeth helped Old Gask (Laurence the sixth laird of Gask) hide in the moors near Birkhall for six months under the name of ‘Mr. Whytt,’ while his son, the seventh laird, took the name of ‘Mr. Brown.’ A passage was arranged for them, and other prominent Jacobites, to Sweden, where they landed in October 1746. The escape was planned by Elizabeth Gordon of Birkhall as recounted below in a letter to Gask’s wife. They later fled to France, and set up a more permanent residence. They were allowed to return home in 1763 to Gask, although they were still considered outlaws, and their attainder was not reversed.

Madam –

The bearer, John Glass, tould me you asked him for a mare I should have of Gasks. When I had the honour of seeing him first, he had a big brown mare. He desired me either to sett her att liberty in the hills, or send her to any place I thought she was safe in. Andrew Forbes, younger of Balfour, came here two days after I gott that mare. He took her along with him and put her into Parks in the Mearns. One Baillie Arbuthnott att Edinburgh proved the mare to be hiss. Your nephew the Master of Strawthallan knew all the story and seed the threatening letters I gott about her.

My nephew Abergeldy when he has the honour of seeing your ladyship will inform you likewise. Andrew Forbes sent me an account from the time off Culloden to August for keeping the mare in Parks, which account I have not paid nor do I desire to pay, because 1 think it reasonable the gentleman who has the nag ought (to) pay that himself. If you please to inform yourself concerning the mare, you will find all to be Truth I have wrote you. All 1 have belonging your husband is a silver snuff box, which he oblidged me to take as a memorandum off him. Whenever you please to call for it, I have it ready. No doubt there might have been some small things lost, as I was oblidged to remove them oft times from place to place. If it pleases God to send Gask to his Native Country, he will do me the justice and honour to acknowledge me one of his friends. His watch which I caused mend, he sent an express for it two days before he left Glenesk. I seed a letter from a gentleman, written from Gottenborg, who writes me Mr. White and Mr. Brown is in very good health. I trust in Almighty God you’l have the pleasure off seeing them in triumph soon, and I am with regard and esteem

Your Ladyship’s most humble servt.

ELIZA GORDON

Laurence the seventh laird of Gask had a daughter Carolina who wrote great Jacobite laments, written to cheer the wounded spirits of her father and grandfather, who never really recovered after the rebellion. Her most famous song was ‘Will Ye No Come Back Again?’ a lament to Bonnie Prince Charlie.

Bonnie Chairlie’s noo awa’,

Safely ower the friendly main;

Mony a heart will break in twa’,

Should he ne’er come back again.

Figure 4.18: Carolina Oliphant and son William

Figure 4.18: Carolina Oliphant and son William

It is time now to leave the Jacobite cause and to return to Peter Gordon the eldest son of Captain Charles and Rachel Gordon. This Peter was to become the eleventh laird of Abergeldy

I googled the Abergeldy castle because it’s currently at risk of falling into the river.

This was one of the most interesting and well written pieces of history I’ve ever read. I really enjoyed it.

A superb account. I was very Interested in Joseph Gordon of Birkhall and his wife Elizabeth. Their son Charles Gordon became an Excise Collector in Montrise then Kelso and is my ancestor. Many thanks.